http://ledger.southofboston.com/article ... life02.txt

COMMENTARY - DON’T STOP BELIEVIN’ - ‘Sopranos’ write-ups off-key about Journey

By JOHN ZAREMBA The Patriot Ledger

‘Sopranos critics, you disappoint me. You are a smart and observant lot, but several of you made some glaring errors in your reviews of the series finale.

So we’ll set the record straight right here: Journey is not a hair-metal band, and ‘‘Don’t Stop Believin’’’ is not - I can’t even believe I have to say this - a ‘‘power ballad.’’

Journey is an arena-rock band, and its 1981 hit, the musical backdrop for our last look at Tony Soprano, is the genre’s signature piece.

But bloggers and TV writers love to over-reach. Some, in their quest to find irony in David Chase’s choice for the series’ final song, practiced a bit of revisionist musical history.

Journey: Hair band. ‘‘Don’t Stop Believin’’’: Power ballad.

Nonsense.

Let’s break this down and define the terms in question:

Hair metal: Some artists and fans take this as an insult. The proper name for the genre is ‘‘’80s glam.’’ It reached its golden age around 1987-88. Poison convinced legions of young men that neon pink was cool, Tawny Kitaen played a human hood ornament in Whitesnake’s ‘‘Here I Go Again’’ video, and Def Leppard’s ‘‘Hysteria’’ was outsold only by bread and water.

While those bands were having all the fun, Journey was on its deathbed.

Drummer Steve Smith and bassist Ross Valory, the rhythm section in the band’s classic lineup, were gone. Steve Perry’s solo album had been a huge hit two years earlier, and the band’s 1986 release, ‘‘Raised on Radio,’’ was a weak follow-up to the multi-platinum ‘‘Escape’’ (1981) and ‘‘Frontiers’’ (1983).

Glam bands either were good-looking or ugly guys who painted themselves to look like women. Journey, a band I love in the most un-ironic way possible, was an unfathomably dorky-looking group.

Just watch the videos. Steve Perry grew a creepy mustache in the middle of the band’s Frontiers tour. Neal Schon had an afro that rivaled TV painter Bob Ross’, and then he cut it, glued some sunglasses to his face and ended up looking like a greasy Ferrari driver.

And why, why, why did they put Valory in solid-colored jumpsuits?

Then there’s the attitude. Glam bands were the bands of party animals: ‘‘Let’s drink and do drugs all night and get the good-looking blonde to take her clothes off.’’

Journey, in its prime, was the band that people’s geeky older brothers liked: ‘‘Let’s listen to Journey and drink Cokes all night and play text-based adventures on my Apple IIE.’’

The bands’ attitudes are clearly reflected in their lyrics. Poison instructed women to talk dirty to them. Journey pledged fidelity and begged women to come back.

Glam bands did not concern themselves with fidelity or romantic longevity. They concerned themselves with making sure the good-looking women had backstage passes.

Journey is in no way a glam band, and I’ll never understand why anybody thinks they are.

It’s just as silly to call ‘‘Don’t Stop Believin’’’ a power ballad. Yes, Journey wrote some fine power ballads, but ‘‘Don’t Stop Believin’’’ is not one of them.

Back in the early ’80s, like a team of scientists researching the cure for cancer, Journey and several of its contemporaries reached a musical breakthrough worthy of the Nobel Prize: They figured out that if you write love songs with airy keyboards, cranked-up guitars and grand choruses, you had a hit on your hands.

There were lots of these hits. Certain people were put in certain moods, and much of the nation’s under-25 population was conceived. Even the guys in Foreigner and REO Speedwagon got lucky. They want to know what love is, and they can’t fight this feeling any longer.

‘‘Don’t Stop Believin’’’ isn’t even a love song: It vaguely tells the story of two people who evidently got on a midnight train and went somewhere to do something. Along the way they are instructed by Journey that they are not to stop believing. Or believin’. Either way.

The lyrical narrative is pretty unspecific, and that’s fine, because what makes the song great is not the story but the style: Jonathan Cain played a great piano hook, Steve Perry sang really high and Neal Schon played the guitar really fast. Taken literally, the song is very bright and optimistic and it makes people feel good.

Power ballads are slow and heartbroken. The guy lost the girl. The guy got the girl back, but only after some painful ordeal. Or in a few cases, the guy is a ridiculously famous rock star on the road, and he’d trade all the fame in the world for a night back home with his woman. (Awwww.)

‘‘Don’t Stop Believin’’’ just doesn’t work as a power ballad. It’s an anthemic, mid-tempo tune that’s not about a girl or the strain of life on tour.

It’s deliberately unspecific and really not about much of anything, which may explain why Chase chose it for the ‘‘Sopranos’’’ last moments.

You can believe that Tony lived, you can believe that Tony died. Just like you can believe that ‘‘Don’t Stop Believin’’’ is about young ambition, or a desperate last grasp at a pipe dream.

By now, it should be pretty clear that all Chase wanted to do is to leave us unsure of what it was we shouldn’t stop believin’.

John Zaremba may be reached at jzaremba@ledger.com .

Copyright 2007 The Patriot Ledger

Transmitted Saturday, June 16, 2007

"Don't Stop Believin'" is not a power ballad!

Moderator: Andrew

3 posts

• Page 1 of 1

"Don't Stop Believin'" is not a power ballad!

Here's an interesting article I found over at The Journey Forums and it's what I've been saying for years.

My blog = Dave's Dominion

-

conversationpc - Super Audio CD

- Posts: 17830

- Joined: Wed Jun 21, 2006 5:53 am

- Location: Slightly south of sanity...

Cheers for that Dave. Here's another article which defended Journey after the Sopranos finale was aired. This is by the music critic of the New York literary magazine Salon.com. He even argues that: "Journey were a lot closer to the Ramones than they were to Led Zeppelin." The comments section is a good read too, by the way....

http://www.salon.com/ent/audiofile/2007 ... index.html

START BELIEVIN'

"As a longtime Journey fan, I was pleasantly surprised to hear the band's rousing "Don't Stop Believin'" play out over the last shot of "The Sopranos" finale. But that surprise quickly turned to frustration as the Web started filling up with anti-Journey sentiment in response to the use of the song.

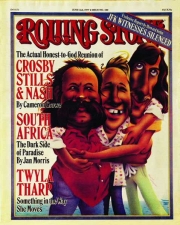

The bloggers' antipathy toward Journey isn't exactly unexpected, though. Critical distaste for the band goes back a long way. Rolling Stone's two-star review of the band's 1981 breakthrough "Escape" -- featuring "Don't Stop Believin'" -- calls the album a "triumph of professionalism, a veritable march of the well-versed schmaltz-stirrers." The Village Voice's Robert Christgau wrote the following about 1983's 6 million-selling "Frontiers": "Just a reminder, for all who believe the jig is really up this time, of how much worse things might be: this top 10 album could be outselling 'Pyromania,' or 'Flashdance,' or even 'Thriller.'" Even a positive customer review on Amazon.com slaps the dreaded "corporate rock" label on the band.

I sort of don't get why Journey are typically derided as slick and soulless. The idea that a heavily produced sound is necessarily lacking in emotion is plainly false. The sonic atmosphere of "Abbey Road" is just as glossy and seamless as anything Journey ever recorded; likewise Nirvana's "Nevermind." And why, exactly, is a punk-rock-style decision to just plug in and play any less calculated or any more authentic than Journey's choice to overdub extensively and give the music a synthesized sheen?

Journey were actually making punchy pop-rock designed to get across quickly. In a weird way, it wasn't that different from punk. Consider this: On the six studio albums Journey put out during their peak years of 1978-86, the band recorded only seven songs longer than five minutes. On just three albums before the band's best-known lead singer Steve Perry joined, 12 songs stretched past the same mark. Journey consciously scaled back, determined to pack as much punch into each single as possible. Hence, the grand, glowing sound of their music, thick with guitars, booming drums, Perry's soaring, multitracked vocals and hook after hook. Nothing is extraneous. In their cool efficiency and pop concision, Journey were a lot closer to the Ramones than they were to Led Zeppelin.

Similarly, the idea that Journey's music is marred by the virtuosity of Perry's insanely flexible and wide-ranging voice and guitarist Neil Schon's flashy technique is another boring bit of punk-rock dogma. Technical ability is not inherently inimical to emotion. If it were, jazz and classical music would have to be dismissed outright. And as with the band's lushly produced sound, Journey's technical facility was always in the service of the song. "Don't Stop Believin'" is a case in point: Schon's tricky rapid-fire picking at the 51-second mark beautifully sets the stage for the rest of the song, his muted sound mimicking the stifled emotions of the lyric's protagonists. Later, his eight-bar solo is a marvel of melodic precision, leading perfectly into the chorus that follows. Perry's rousing vocal performance works much the same way. "Don't Stop Believin'" is about desperate hope -- "living just to find emotion." Accordingly, the Olympian high notes that Perry affixes to the end of the line "Hiding somewhere in the night" are a suitably inspiring match for the song's message of hopeful perseverance.

The carping of persnickety "Sopranos" viewers aside, the recent attention has been good for Journey (who, minus Perry, still regularly tour). As of this morning, the band's greatest hits collection was holding down the No. 53 spot on Amazon.com's album sales rankings; "Don't Stop Believin'" was at No. 22 on iTunes. These listeners are learning what millions of listeners unconcerned with what's hip have known for years: Journey's a band to believe in.

-- David Marchese"

http://www.salon.com/ent/audiofile/2007 ... index.html

START BELIEVIN'

"As a longtime Journey fan, I was pleasantly surprised to hear the band's rousing "Don't Stop Believin'" play out over the last shot of "The Sopranos" finale. But that surprise quickly turned to frustration as the Web started filling up with anti-Journey sentiment in response to the use of the song.

The bloggers' antipathy toward Journey isn't exactly unexpected, though. Critical distaste for the band goes back a long way. Rolling Stone's two-star review of the band's 1981 breakthrough "Escape" -- featuring "Don't Stop Believin'" -- calls the album a "triumph of professionalism, a veritable march of the well-versed schmaltz-stirrers." The Village Voice's Robert Christgau wrote the following about 1983's 6 million-selling "Frontiers": "Just a reminder, for all who believe the jig is really up this time, of how much worse things might be: this top 10 album could be outselling 'Pyromania,' or 'Flashdance,' or even 'Thriller.'" Even a positive customer review on Amazon.com slaps the dreaded "corporate rock" label on the band.

I sort of don't get why Journey are typically derided as slick and soulless. The idea that a heavily produced sound is necessarily lacking in emotion is plainly false. The sonic atmosphere of "Abbey Road" is just as glossy and seamless as anything Journey ever recorded; likewise Nirvana's "Nevermind." And why, exactly, is a punk-rock-style decision to just plug in and play any less calculated or any more authentic than Journey's choice to overdub extensively and give the music a synthesized sheen?

Journey were actually making punchy pop-rock designed to get across quickly. In a weird way, it wasn't that different from punk. Consider this: On the six studio albums Journey put out during their peak years of 1978-86, the band recorded only seven songs longer than five minutes. On just three albums before the band's best-known lead singer Steve Perry joined, 12 songs stretched past the same mark. Journey consciously scaled back, determined to pack as much punch into each single as possible. Hence, the grand, glowing sound of their music, thick with guitars, booming drums, Perry's soaring, multitracked vocals and hook after hook. Nothing is extraneous. In their cool efficiency and pop concision, Journey were a lot closer to the Ramones than they were to Led Zeppelin.

Similarly, the idea that Journey's music is marred by the virtuosity of Perry's insanely flexible and wide-ranging voice and guitarist Neil Schon's flashy technique is another boring bit of punk-rock dogma. Technical ability is not inherently inimical to emotion. If it were, jazz and classical music would have to be dismissed outright. And as with the band's lushly produced sound, Journey's technical facility was always in the service of the song. "Don't Stop Believin'" is a case in point: Schon's tricky rapid-fire picking at the 51-second mark beautifully sets the stage for the rest of the song, his muted sound mimicking the stifled emotions of the lyric's protagonists. Later, his eight-bar solo is a marvel of melodic precision, leading perfectly into the chorus that follows. Perry's rousing vocal performance works much the same way. "Don't Stop Believin'" is about desperate hope -- "living just to find emotion." Accordingly, the Olympian high notes that Perry affixes to the end of the line "Hiding somewhere in the night" are a suitably inspiring match for the song's message of hopeful perseverance.

The carping of persnickety "Sopranos" viewers aside, the recent attention has been good for Journey (who, minus Perry, still regularly tour). As of this morning, the band's greatest hits collection was holding down the No. 53 spot on Amazon.com's album sales rankings; "Don't Stop Believin'" was at No. 22 on iTunes. These listeners are learning what millions of listeners unconcerned with what's hip have known for years: Journey's a band to believe in.

-- David Marchese"

-

Matthew - Stereo LP

- Posts: 4979

- Joined: Fri Jul 28, 2006 2:47 am

- Location: London

It's amazing isn't it? All recent press about the song refers to it in this manner. I completely agree, DSB isn't even CLOSE to a power ballad. Numnuts!

You Only Go Around Once - GollyWally

-

GollyWally - Ol' 78

- Posts: 100

- Joined: Thu Jun 21, 2007 4:08 am

- Location: Atlanta, GA

3 posts

• Page 1 of 1

Who is online

Users browsing this forum: No registered users and 11 guests